Have you ever been convinced of a fact, only to find out it was entirely wrong? This happens to many, but what if this shared misremembering affects millions of people at once?

This is the puzzle behind the “Mandela Effect,” and one of its strangest examples is that famous line from Snow White. Why do so many people remember “Mirror, mirror on the wall”… when the line was never spoken that way?

Wait, It Wasn’t “Mirror Mirror”?

I know what you’re thinking: “Of course it was ‘Mirror, mirror’—I can hear it in my head!” But pull up the classic Disney animation, and you’ll hear something else entirely. The actual line is: “Magic mirror on the wall.”

This mind-bending detail has left generations of Disney fans scratching their heads. If you’re feeling a little disoriented right now, join the club!

What Exactly Is the Mandela Effect?

The Mandela Effect refers to a phenomenon where large groups of people remember something differently than how it actually happened. It’s named after Nelson Mandela, because many people—myself included—distinctly remember hearing he’d died in prison in the 1980s. Spoiler: He didn’t. He was released and became the President of South Africa.

- Other classic examples? “Berenstain Bears” (not Berenstein!), “Febreze” (not Febreeze), and “Looney Tunes” (not Looney Toons).

- Researchers and psychologists, including experts at the American Psychological Association, agree that memory is surprisingly malleable.

Why Do Our Memories Fail Us Like This?

So why can’t we trust our own brains? Most scientists point to a few culprits:

- Confabulation: Our minds fill in blanks and create details that make stories feel right—even if they’re wrong.

- Social Reinforcement: If everyone around you remembers something a certain way, you’re more likely to go along with them.

- Media and Pop Culture Echoes: Parodies, references, and repeated quotes in TV shows, movies, and even greeting cards reinforce the wrong memory until it feels like fact.

Have you ever played a game of “telephone”? That’s basically what’s happening—except it’s your brain playing tricks on itself!

Why Did “Mirror Mirror” Stick?

There are a couple of fascinating reasons why “Mirror, mirror” feels so natural—even when it’s not what Disney’s Evil Queen actually said.

- The original Brothers Grimm fairy tale does use “Mirror, mirror” (in German: “Spieglein, Spieglein an der Wand…”).

- Hundreds of books, cartoons, and pop culture references have quoted “Mirror, mirror” over the years.

- It just sounds catchier—there’s a rhythm to the repetition.

So even if the movie script says “Magic mirror,” the collective memory of “Mirror, mirror” won out. Our brains like patterns and catchy phrases, so they subtly edit the details for us.

Is There More to the Mandela Effect?

Some people love to theorize about alternate realities or glitching timelines. Is it possible that we all shifted to a universe where “Magic mirror” was always the line? I’ll let you decide if that’s plausible or just a great sci-fi plot.

But the mainstream consensus among psychologists is a lot more down-to-earth. We misremember things because our memories are flawed, suggestible, and biased by repetition.

How Can You Outsmart Your Brain?

So, what can you—or any of us—do about it? Here are a few tips:

- Double-check before you “know for sure.”

- Be skeptical of memories repeated by groups.

- Enjoy the quirks of collective memory—it’s what makes us human!

The Bottom Line: It’s Not Just You

If you’ve ever confidently quoted “Mirror, mirror on the wall,” you’re not alone—and you’re not losing your mind. The Mandela Effect shows just how easy it is for all of us to “remember” things that never were.

Next time you catch yourself in a memory mix-up, smile and remember: sometimes, the real magic isn’t in the mirror—it’s in our minds.

VPNs: Do You Really Need One or Is It Just Marketing Hype?

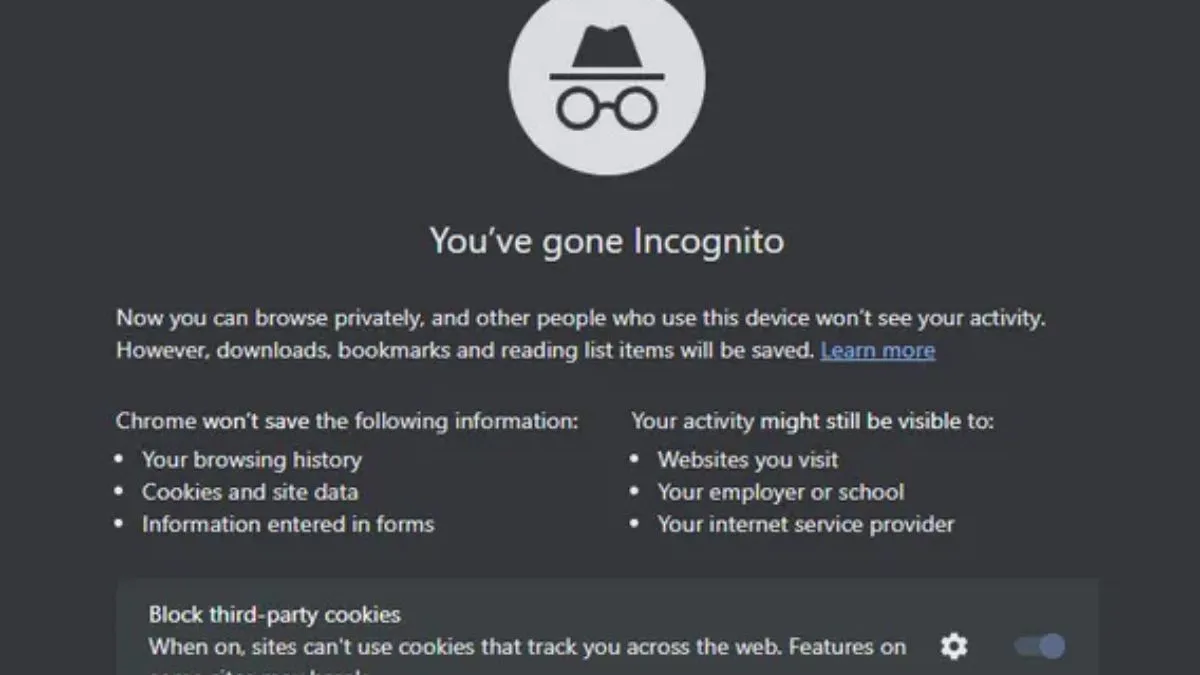

Incognito Mode: Does It Actually Hide Your Browsing from Your ISP?

Subscription Fatigue: How to Find and Cancel Subs You Forgot About

5G Conspiracy: Why The Towers Are Harmless (Physics Explained)

Wireless Charging: Is It Less Efficient Than Plugging In?